The subject of this issue of Entrentre is a drawing by architect Charlotte Erckrath. The drawing was first developed for an exhibition at Modtar Projects in Copenhagen, 2012. It was installed next to the entry of the main exhibition space at the top of a small wooden stairway. The drawing depicts this entryway and a mechanical device Erckrath developed for the site.

Charlotte Erckrath works with drawings, texts and the making of spatial devices. In her work architecture is discussed as an open territory. Her interests range from visual and measuring devices to descriptive geometry, pictorial exploration and theories of architectural drawing. Erckrath currently holds a position of an assistant professor at the Bergen Architecture School in the field of DAV (‘Den andre verden’ /The Other View).

Interview by Anne Friis, March 2019.

Anne Friis (AF): The drawing contains plans and elevations of a mechanical device that you exhibited at Modtar Project Room. What is this mechanical device? How does it function? What is its purpose?

Charlotte Erckrath (CE): The project starts from an idea of narrative and spatial imagination, a narrative that is concerned with inhabitation of space over time. The mechanical system explores how space can be activated in its capacity to reflect an inhabitant’s presence by picking up the small disturbances in the building´s fabric such as the moving of floorboards under an intruder’s weight.

An important element of this narrative is the sense of being inside which includes the subsequent dilemma of a phenomenological problem: that we are as bodies perceiving space as a tactile and acoustic presence and at the same time as a visual experience. In this project I am interested in reflecting on the spatial contradiction that arises, when we sense space as something that is constructed within the body as an interior experience that at the same time presents itself as a visual exterior reality.

The question is how architecture could be a reflection of this phenomenological spatial experience. The notion of reflection is suggested as a literal idea of mirroring imagined processes of perceptions and events with the aim to construct an architectural response to our bodily presence in space. The mechanism performs as an imaginative language, where levers and hinges articulate how events in space might be related and subsequently feedback a response.

The device inhabits a situation around a doorframe, which connects a staircase in a little backyard house with an upstairs living room. It is attached to an interactive and responsive element of the architectural fabric: The floorboards just in front of the threshold are giving away to the weight of the body in the moment prior to entering the room. Upon entering the room, the impact on the floorboards is transferred to a hydraulic system, which records, stores and delays the energy for a feedback in a bladder. The part entitled ‘waiter in the threshold’ initiates a subtle push into the mechanical system of levers, which continues by several hinges and levers into the shadow besides the doorframe and further across the threshold. Outside of view, inside the room, the mechanism brings a pendulum into motion, which by shifting sideways activates a small air pump. The air bladder that subsequently fills with air would be located in the weight of the pendulum but has neither been made nor detailed. The pendulum mechanism refers to time and gravity in a non-straight-forward manner. It is hocked to the hydraulic system, which operates as both driver and resistance. The feedback mechanism functions like an overfill valve, but whatever the feedback may be, remains unresolved. When filled to a certain extend, the amount of air squeezes through a system of channels to drive an undefined and non-built acoustic action (to be continued) - a delayed and accumulated response the spatial impact of the inhabitation. The key idea for the conception of this series of mechanism was to achieve a system of events with a peculiar autonomy in the way it operates within its own time.

The design language and materiality reminds of some handcrafted clockwork mechanism or scientific measuring instruments. Even more it may be similar to mechanism hidden in mechanical cabinets that perform surprising functions such as some of the royal furniture designs from the Röntgen brother's workshop. The interweaving of the built space with mechanical operations was an idea that inspired this work.

AF: The drawing is multi-layered. Both practically and in the sense that it contains many different forms of drawings such as plan and elevation, a folded map and two different types of text. Can you say something about the development of the drawing? The use of narrative writing is not usually seen in architectural drawing. Which potentials do you see in interweaving architecture and literature?

CE: At the time the device was made, the drawing was used as a planning tool to think through the hinges and levers: Where they would be placed precisely, how they would interact and be made. The making of the device was a process of resolving a system of relationships that would communicate themselves through performing. While not being developed operational in time as a fully functioning device, this idea and its consequence on the architecture remains unintelligible due to the fragmented state of the installation.

The drawing came in as an intention to bridge the gap between the made and the idea. It holds the potential for a reading beyond the appearance of the device. By constructing a map that contains annotations for the individual agents and a suggestion of their relation to the narrative, the text questions the objectively visible and opens up for other levels of reading.

Through language the drawing allows to work with the initial ideas about the experienced space and to establish the relationship with these thoughts. The quality of the map as a mental concept is employed in this project for the imaginative aspects that the work contains and it opens a level of interpretation. In difference to the actually made device, the drawn parts loose some of their properties to abstraction, while at the same time some other notions become more persistent. They still do not perform, but through the drawing the possibility of their performance can be suggested.

Looking at the text on this map, it is twofold. One layer addresses directly the drawn elements by naming them and pointing at their function in an overall mechanical system. The other layer refers to the narrative of sensing one´s own spatial presence as an idea of reflection of different moments in time. While the annotation text operates within the logic of reading an architectural drawing, the narrative assembles in different ways as it is being read throughout the map. The text seems to develop along a chronology of events, but the common linear structure of reading is interrupted through a spatial displacement of the text on the map. This requires that the reader assembles the text anew and the reading of the drawing suggests it own time.

To embed writing within architectural drawing practice in this way introduces a sense of time. Employing narrative includes the subjective situation, around which the drawing is constructed and engages the context beyond the apparatus into a much broader reading. In drawings that conform to orthogonal parallel projection such as the convention of architectural plan and section theses are aspects that are usually excluded. To emphasize on subjective experience and time in architecture could be the actual potential for bringing writing and drawing together.

AF: Which role do the folds play in the drawing?

CE: They are a consequence of hinging the sheets of paper that contain the individual sites into one continuous spatial narrative. This map-like construction aims at relating the places through the rules of orthogonal projection and folds the three-dimensional space into the drawing plane. The folds follow the logic of a hinge between two projections. I am interested in this idea of the hinge as they are opening a realm for imagination. Reading plan and elevation together encourages constructing an understanding of the object in the mind. The hinge in that way is an agent to construct space.

There are some additional folds that add a sense of spatiality to the drawing. They start to operate together with the text, more like the folding of a page of a book, which is about revealing the space or the narrative over time. The drawing does not present itself fully at a single moment, instead there are different ways to come across it.

By drawing only what matters about the space of the doorframe, the folded map allows to bring the threshold of the doorframe into a new relationship. Gaps are appearing and the map is not fully consistent to the actual site. My map transforms the site and constructs a new idea of the entryway and how you encounter it.

AF: In order to eliminate mistakes caused by misreading of the construction drawing in the building process traditional architectural drawings aim at clarity. Contrary to this your drawing contains a wealth of ambiguities and even contradictions. For example the two different types of text (or perhaps one could say the two different voices in the drawing) constantly tell different stories about what the space is.

CE: The annotation text aims at being relatively clear about the agency of each part. They should be read as performers that interact. The other text is quite vague, giving hints to other moments in time and to the subjective experience of the space the device inhabits – maybe my own (imagined) experience in that space. This text in some way operates outside of time or in its own time. It may read contradictory as it composes notions, which do not happen simultaneously, but are part of a memorized time space collage.

When the drawing, after being used as a device to construct the mechanism, transformed into a map, it turned into a mental construction. I enjoy the way it becomes this ambiguous object that opens up questions rather then answering them. The reading of the map as a narrative or a poetic piece of writing occurred as one possible speculation.

Some parts in the drawing are more evolved, while others are only sketched in or even missing, like the white spots on a cartographic map that open up for imagination and further exploration. As a way of keeping the drawing alive, to me these open ends hold a desire for further agents to be added, which potentially participate in the interaction, enable it, block it. As a process tool, the drawing can be very powerful both to establish and plan what is built, but even more to think and speculate about possibilities and desires.

But what if it could be translated into a site for the device and how? A story by Borges, On Exactitude in Science, mentions a society of geographers that constructed maps to the level of detail as the land. Finally the map became one and the same as the land it surveyed and due to impossible use of the land, the country fell into decay. What is fascinating about this story is the speculation on the relation to the real that is within the nature of drawing maps. One may try to only record in a map what is there, but as this changes constantly, it also offers itself as a territory to speculate into the future.

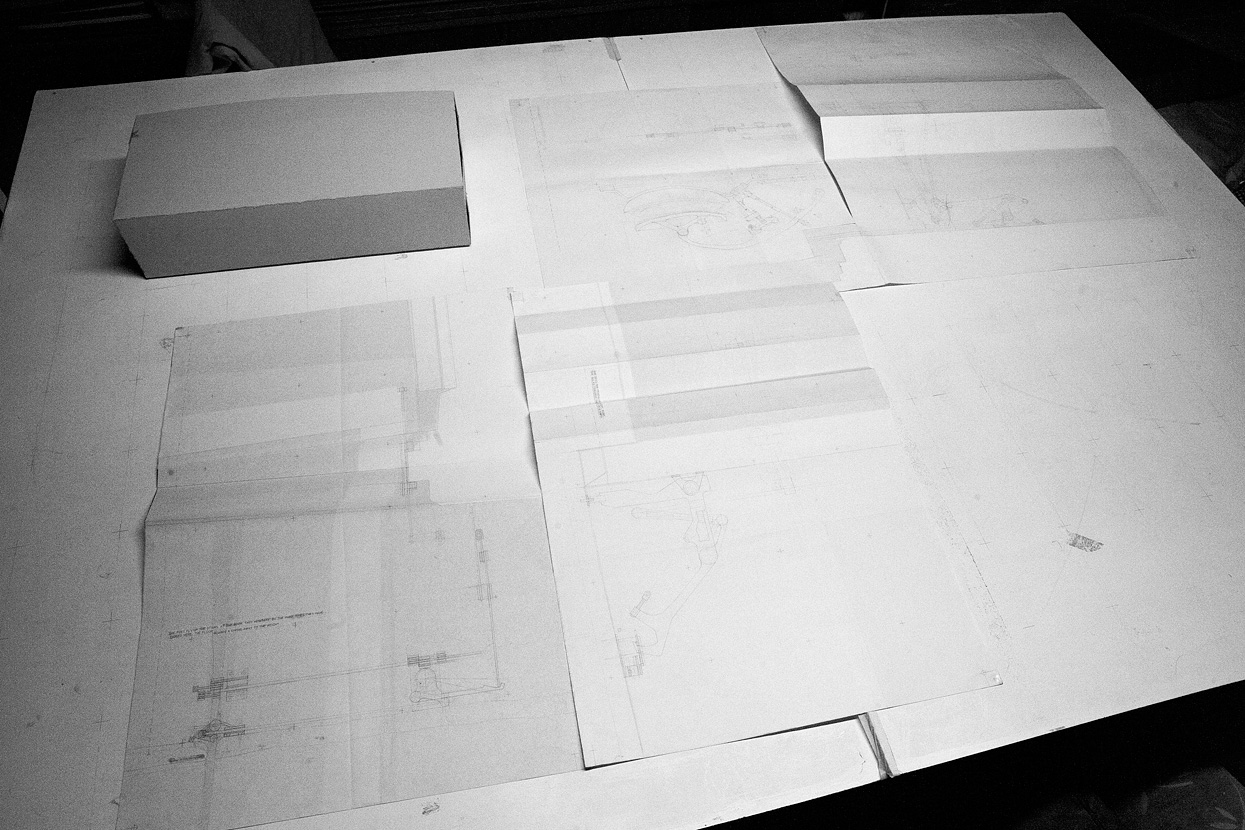

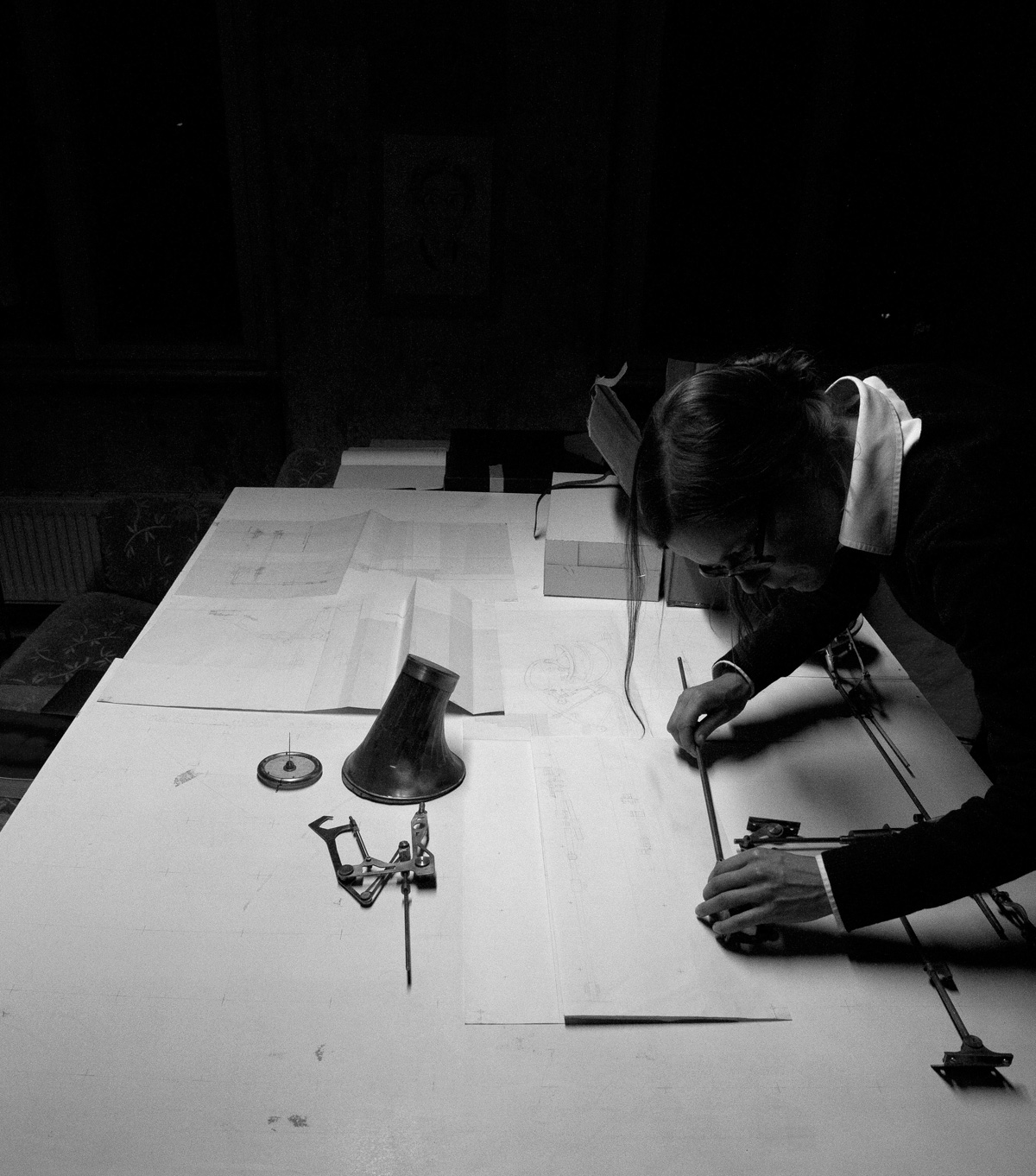

AF: To accompany the interview you have prepared a series of photos of the drawing. Representing a delicate pencil drawing digitally is never easy, and in case of this project it is further complicated by the drawing's spatiality. How have you been working with the drawing for this online presentation?

CE: I always saw the drawing as an artefact, as something to be grasped as a whole before entering into the detail. This quality is difficult to represent on a screen, but working with the content eventually led to constructing a photographic journey through the drawing.

The first attempt used a parallel view to the drawing, which reveals more of the contradictions of the folded map and suggests many possibilities within it by the folds and gaps that operate within a space of multiple dimensions.

For this webpage, finally an oblique view was chosen to emphasize not only the subjective view of the reader but also the drawing as artefact. The surface of the paper has its own presence, when looked upon in an oblique way. In contrary the parallel view seems to confuse the drawing plane with the plane of the screen and the drawing loses its material reality or even spatiality. In this case the paper actually adds a disturbing layer, because it rarely reproduces evenly.

The linear journey became a tool to consider the reader in the drawing. At the same time it transforms the space in the map when passing the folds and the hinged drawing planes, while the shifting from horizontal to vertical to cross-section undermines the coherence to a spatial linearity. As the journey revisits a place in the map additional parts of the drawing appear, which have been initially hidden in the folds. Other areas become at times continuous or discontinuous.

Since we share work mainly via screens, these issues become very relevant. Compared to the digital drawing the hand drawing certainly has disadvantages when it comes to being represented in this media. It is much less capable to adjust to the scale of the screen.

AF: I have the impression that you have reworked the drawing several times over the years after the exhibition in 2012, and that you do not seem to consider the drawing as finished, but rather as a work in constant transition. This iterative work process seems to recur in other of your works, for instance the ongoing restoration and transformation of the workspace at Triftstrassse 19A, Halle(Saale)(together with Maik Ronz) and the research derived from observations of Helmut Newton’s photograph ‘Self-portrait with Wife and Models’ from 1981. Can you say something about your work process in this project and in general?

CE: I guess the idea of the unfinished is something I have learnt to embrace as a quality over time. It seems that whenever progress is made, new opportunities arise or new questions open up. Like with this drawing project, it was not initially intended as part of the installation at Modtar. Instead it was a part of the fabrication process.

I have always struggled with the verbal communication of the work. Describing it would not do the job as it consolidates rather then opens the work for imagination. The map was an attempt to bridge this gap. If it does open up the space to imagination, then maybe it works. It depends on the reader, I suppose.

As with the research on the Helmuth Newton photography, the questions that have departed from it rotate, meet other fields of my practice and return to it. Certain interests have developed from this initial study and it seems fruitful to pick up some of the open ends. There are a lot of artefacts in my storage from that time, which have a quality on their own. I like the idea that they are tools, sometimes in the literal sense to produce other artefacts and sometimes tools for thinking or questioning.

The work at Triftstr in that way may also be understood as a tool to question the use of this space. We have had different ideas about what the space might be and how we could use it. It was not intended as unfinished. But finally the unfinished seems to be its actual quality that continues to narrate the actions taken upon it. This has also a lot to do with the time spent, which connects the time of working with the accumulated and processed material. I guess it would be far less interesting if it were finished. It is like editing the white spots out in the map.